Transcript of the above article in The Living Tradition April / May 2021

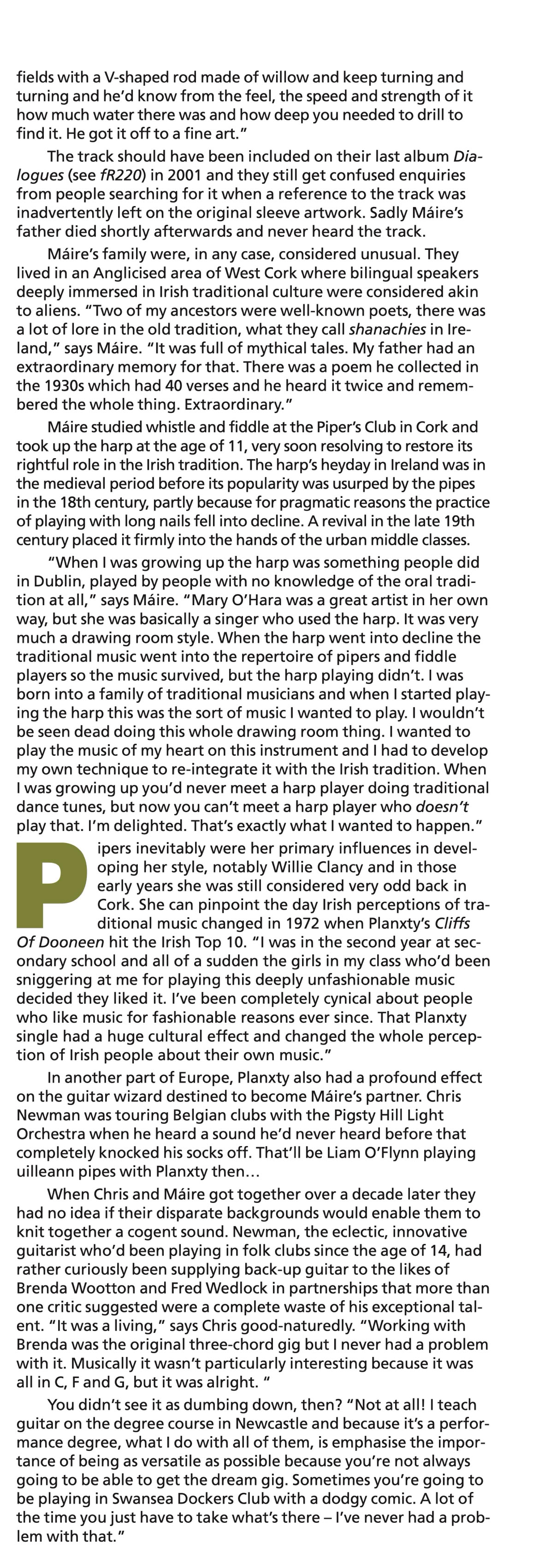

Máire Ní Chathasaigh & Chris Newman

By Fiona Heywood

“Virtuosic, fascinating, dramatic, original, inspired, gloriously adventurous, dazzling, brilliant, stunning, impassioned, electrifying, bewitching, moving, achingly beautiful, influential, revered, unique...” This is how harper Máire Ní Chathasaigh and guitarist Chris Newman have been described over the years by the various musical publications that have featured their work. And those of us who have been lucky enough to experience their music first-hand know that this is no exaggeration. Máire and Chris are two awe-inspiring musicians whose music together is something very special indeed.

Coming from two very different backgrounds, they have found a way to be completely themselves in their music, and yet their synergy is quite breath-taking, making them very much in-demand in Ireland, in the UK, in the US, and all over the world. I asked them both a bit about their personal journeys in music, their introduction to traditional music in particular, and also about their journey together as a duo.

Máire goes first… She grew up in Ballinascarthy and then Bandon in Co Cork, steeped in the Irish tradition, her mother, grandmother and uncle being fine singers. “My mother (now 98) taught us songs from when we were really tiny, and taught us all simple Irish dancing steps too, and used to play slides and polkas on the mouth organ for us to dance to. My father wasn’t a great singer himself, but he had a large store of songs and poems in the Irish language and an amazing memory for the seanchas (traditional lore) and poetry that had been preserved in his family – he could remember 40-verse poems that he’d heard only a couple of times in the 1930s! There were a number of minor Irish-language poets in his family and we grew up imbibing lore about them and learning various poems they had written, both published and unpublished. We felt – and still feel that we are merely the most recent links in the transmission of traditional lore, song and music from many past generations and its bearers into the future.”

Máire has rightly been called “the doyenne of Irish harpers”, but the harp was not her first instrument – she began on the piano, and also played the fiddle and the whistle. “My parents were mad about music and my mother in particular was willing to buy us any instruments and pay for whatever tuition we wanted, within reason. Sometimes she bought instruments because she liked them herself and then left them lying about in case one of us decided to take a shine to them. The harp she bought worked out very well, but the banjo she bought languished unloved in a corner until she finally relinquished all hope of one of us taking it up and sold it again! My sister Nollaig and I both started playing the fiddle and the harp. She really took to the fiddle and I really took to the harp and we both ended up playing those instruments professionally! Our younger sister Mairéad plays both. We all played the piano and whistle and we all sang too (including my

brothers), so it was a noisy house, with people playing in practically every room and rows about whose turn it was to have access to a particular instrument!”

As a teenager, and with no harper role models, Máire began to work out ways of doing things a bit differently, breaking new ground in terms of the repertoire and the techniques she used on the harp, developments for which she is now widely renowned. Until Máire, harp music in Ireland was quite different. She explains more. “I wanted to find and develop a voice on the harp for the traditional music that I grew up with and that was in my heart and soul. At that time, the playing of Irish dance music on the harp in an authentically ornamented way and with the nuances of rhythm, tone and articulation essential to that style, was unheard of. The harp had long been used almost exclusively for song accompaniment and for some performance of the music of the old 17th and 18th century Irish harpers, played from the sources in a literal manner, and existed in a world apart to that of the oral tradition. So, fiddling and piping were what I listened to for inspiration in developing the new techniques - particularly in relation to ornamentation - that made it possible for the first time to play Irish traditional music on the harp in a stylistically accurate way.”

I wondered whether Máire’s new approach was well-received amongst the harp fraternity. “I actually got a great reception in traditional music circles,” she told me, “which was very gratifying for a painfully-shy teenager in the 1970s. People said to me many times that they had never thought what I was doing would be possible on the harp, and that they’d always, until that point, thought the harp to be a useless instrument for traditional music! I was made to feel that what I was doing was worthwhile and that I should continue along that path. Older musicians who were considered to be arbiters of taste at the time were hugely supportive and gave me lots of opportunities: people like Séamus Mac Mathúna, Joe Burke, Tony McMahon and so many others. I won the Senior All-Ireland at Fleadh Ceoil na h-Éireann three times in a row during the 1970s and was invited to run a harp class at the Scoil Éigse before the All-Ireland Fleadh in Buncrana in 1976 – the first time that the harp had been included in such an event. The harp world was immensely supportive too, particularly in the person of Gráinne Yeats (though her approach was, of course, very different to mine). I walked on air after she said in her adjudication of the Pan-Celtic Harp Competition that my playing seemed like a reincarnation of the bardic spirit.”

Though clearly coming from a traditional background and learning to play the music by ear, Máire had also learned to play classical music by reading the notes, and did both things side by side - something that she says was quite unusual at that time. As an adult, I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to do that, as I believe the ability to learn equally well by ear or from written music is a big advantage to any musician,” she said. But it was only after Máire had developed her innovative new techniques for playing trad that she had any classical harp lessons. “I started these in my early twenties, when Denise Kelly came from Dublin once a fortnight to teach pedal harp in the Cork School of Music – it hadn’t been possible to get any such lessons in Munster until that time. She really sorted out my overall technique and stressed the importance of codifying fingering patterns. I then found a way of integrating classical techniques with my own ones.”

The combination of these classical techniques and Máire’s innovation with traditional forms has been so successful, in 2001 she won one of the highest accolades for an Irish traditional musician, the Gradam Ceoil for Traditional Musician of the Year - “for the excellence and pioneering force of her music, the remarkable growth she has brought to the music of the harp and the positive influence she has had on the young generation of harpers.” That positive influence has seen several other harpers follow where she led, and the scene today is a very different one.

“I had what seemed in the 1970s to be a romantic hope that the harp could be reintegrated into the oral Irish tradition,” Máire said. “I’m delighted that it has now happened in a big way; bringing it about has been a massive voluntary communal effort by many unsung heroines of the harp world. When I started playing the harp, nobody played Irish traditional dance music on the harp, whereas now it seems to be impossible to find an Irish harper that doesn’t play dance music! Laoise Kelly, Gráinne Hambly and Marta Cook are lovely players of dance music, with a deep knowledge and love of the tradition and their own distinctive styles. And of course, there are hundreds of other very fine harper players of dance music in Ireland alone, and teachers can be found pretty much everywhere. There’s been an explosion of interest in the harp in the last number of years, culminating in the establishment of the umbrella body, Harp Ireland, and the inscription of the Irish harp on the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2019 – driven largely by the herculean efforts of the Chair of Harp Ireland, Aibhlín McCrann, and its various committees. So, the future is very bright.”

While Máire was re-inventing harping in Ireland, Chris Newman was over the sea in England, getting a different grounding in music. Born in Hertfordshire, he spent most of his life in the north of England, and with his mother being a professional actress, he was no stranger to performing – he was already playing the guitar by the age of four! Chris told me a bit of his back story… “I have a brother who’s 10 years older than me. He got a guitar for his birthday one September and I badgered my parents into getting me one for my birthday the following month. I had been ‘put to the piano’ when I was five but really disliked it and preferred the guitar. My parents allowed me to leave the piano behind and concentrate on the guitar. By the time my brother was in his mid-teens, he was well into the guitar and was going to the many folk clubs that existed around that time in the Leeds and Bradford areas. He used to come back from the clubs with new things he’d heard, and initially I simply copied them.”

Chris played his first paid gig in a folk club at the age of 14, and from there went on to play with an amazing array of musicians, in the folk world but also beyond it. He met the terrific Django-style guitar player Diz Disley while still in his teens, and played extensively with him in many of the UK’s folk clubs. “He introduced me to the whole swing jazz world and I learned a great deal from him when I was still pretty young,” said Chris. Through Diz he also met Stéphane Grappelli, and Chris played in his band for a time. He later worked with the west country folk comedian, Fred Wedlock, for eight years, composing the tune for his 1981 hit song, ‘The Oldest Swinger In Town’, producing his records, running his touring band and making many appearances with him on TV and radio. He also worked with such luminaries as Brenda Wootton, Kathryn Tickell and Boys Of The Lough amongst many others.

Describing the kind of music that he plays as “a variety with a capital V,” Chris has been able to master several different styles – from swing jazz to bluegrass to Celtic – and he’s also a mean mandolin player. He began playing fingerstyle guitar (i.e. using his thumb and fingers without any picks) but over the years has moved to a flatpicking style (i.e. with a plectrum). “I played exclusively fingerstyle until I was about 16 when someone gave me a plectrum. I took to it like a proverbial duck to water and over about a 10-year period moved away from fingerstyle. I simply preferred the much greater power available with a flatpick, and I no longer had to worry about breaking nails!” he said.

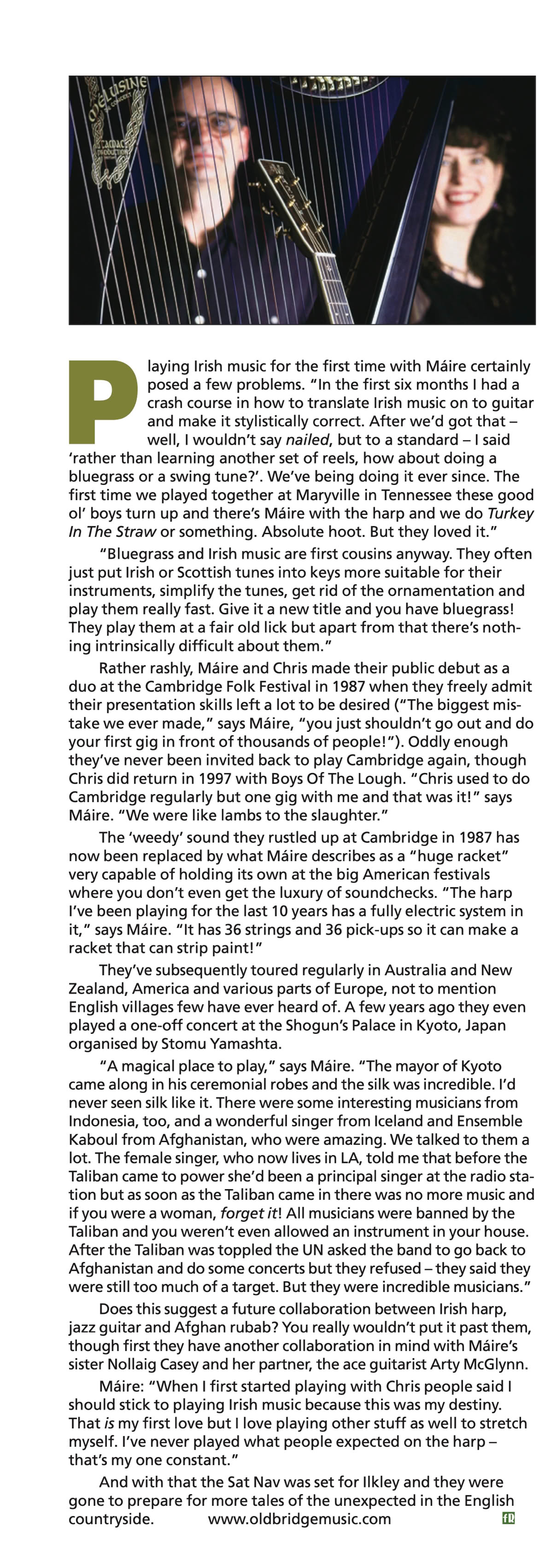

In 1984, Chris was with Cornish singer Brenda Wootton playing at a Celtic festival in Galicia in north-west Spain. Máire was booked as a soloist at the same festival. They met, and a few years later, in 1987, began playing together, which led to Chris adding yet another style of music to his arsenal – traditional Irish. I wondered how he adapted to that style, who he listened to, and what techniques he had to learn that were different to those he was already using.

Obviously Máire was his first port of call for any questions about the music and the way it was played, and Chris was lucky to learn from someone as immersed in it as she is. “Apart from Máire,” he said, “I spent a great deal of time listening to Mary Bergin (the Galway whistle player) recordings. She’s a fantastic example of how to use ornamentation and variation really well and extremely imaginatively. I used to tape her recordings at 15ips in the studio then play them back at 7½ - this meant the key was maintained, although the whistle pitch was reduced by an octave, but the main thing was that the speed was halved so I had a sporting chance of figuring out what was going on!”

“Learning about cuts, rolls and triplets was an eye-opener, but ultimately was just another technique to add to the armoury. In recent years, I’ve spent lots of time working on different technical aspects of playing as I firmly believe they are the key to everything. For the past 20 years or so I’ve been the principal guitar and mandolin tutor at the folk degree course at the University of Newcastle and, as I’m often teaching people who are already pretty advanced players, I’ve found myself looking very carefully at my own techniques and improving them accordingly. I certainly wouldn’t want to be seen as being a slave to technique, but without the basics it’s virtually impossible to play really well in any style.”

Chris says he has always enjoyed playing lots of different types of music, which makes him very difficult to ‘pigeon-hole’ for those who might want to. This comes with some benefits, but also drawbacks. “The core of what Máire and I do together is traditional music,” he said, “but every couple of years since 2003 I’ve been teaching at a huge music camp in east Tennessee which is, to all intents and purposes, a bluegrass festival. I’m not a bluegrass specialist but I enjoy my time there very much, and I just about hold my own! I guess the main benefit is that I’ve never been out of work since leaving school as I’ve always been versatile enough to fit in with most situations. Drawbacks? I’ve found that people like to pigeon-hole musicians – ‘Oh, he’s a Celtic player, she’s into old time,’ etc. I’ve always quite deliberately avoided that. One LP I made with Fred had ‘File under Opera/Punk’ on the back of the sleeve.”

And just when you thought you knew what to expect from Chris, he starts working on something entirely new again. This time it’s the music of J. S. Bach! “This has been my lockdown project,” he told me. “Some years ago, I saw a video on YouTube of a fantastic American mandolinist called Chris Thile playing the Preludio from Bach’s Partita No 3. It’s a really well-known piece written for the violin, so the translation to mandolin would have been relatively straightforward, although still fiendishly difficult to play as well as he did. It got me thinking about whether it’d be possible to flatpick the tune on the guitar in much the same way. This presented a few quite tricky technical issues, but after several months I was able to record it.” (You can watch it if you search for ‘Chris Newman Flatpicking The Partitas’ on YouTube).

Chris is currently working towards releasing a new CD featuring the music of Bach. “When the first lockdown started in March 2020, all our gigs (along with the rest of the planet’s) were cancelled so I found myself with a huge amount of unexpected time on my hands. I trawled the web looking for Bach pieces written for largely monophonic instruments and have spent the past 11 months or so happily working my way through partitas and sonatas written for either violin, flute or cello. The recording’s actually complete, but I still haven’t decided what to put on the sleeve, though I hope to be able to release it soon. Having all this free time has been a fantastic opportunity to really get to grips with this stuff. It’s brilliant music and has been a real challenge.”

I had heard that Chris doesn’t read music, so wondered how he managed to handle something as complex as a piece of Bach by ear. “With difficulty!” he said. “I can’t read music, so the studio Mac’s been an important part of the process as it’s possible to take a recording and slow it down without altering the pitch. It’s not that far removed from what I used to do with the Mary Bergin recordings back in the eighties! I also have a pretty good musical memory.”

In terms of Chris and Máire’s joint performances and recordings, they have successfully managed to incorporate all these different genres, styles and techniques into something that, as Máire says, is “more than the sum of its parts”, and anyone who has heard them perform can attest to that.

“Once we decided we’d have a go it really wasn’t too bad,” said Chris. “The thing we both had to do was compromise, in the sense that I’d sometimes be obliged to play a line which was not at all guitaristic, and Máire often had to do things that most certainly were not harp-like!” Máire continues: “We did a lot of experimentation in the early years, with both repertoire and arrangement. Though Chris had been playing on the English folk scene since he was a teenager, we were really from different musical worlds and put effort into learning about each other’s music. Chris is a fantastic improviser, so we needed to find a way of enabling his abilities in this area to shine. So our sets together have always been a mixture of straight traditional music, the various forms of music that Chris plays, and tunes we’ve composed. We don’t mix the genres together – it’s not ‘cross-over’ music.”

Chris and Máire suspect they were the first harp and guitar duo on the scene, a combination that was certainly unusual then. “According to our agent at the time,” said Máire, “festival and venue promoters were very suspicious initially, as they just couldn’t envisage what a harp and guitar were going to sound like played together. Once they made the leap of booking us, they usually liked what we were doing and thankfully we got more and more work. We really had to create a market from scratch for what we were doing though!”

Both instruments are traditionally seen as instruments for accompaniment, but Chris and Máire take that notion and turn it on its head. They both take the lead, and both also allow the other space to do their thing. It sounds like it happens so naturally but, as is often the case, it is the result of a lot of work. Chris explains: “In the early days we’d spend a long time working out arrangements, giving each instrument space and trying to avoid constantly climbing over each other. In more recent times it’s a much faster process; one of us will come up with a tune and we’ll pretty much instinctively know what to play, and when. And when to play nothing at all!” Máire agrees: “We’re both keen arrangers and are very conscious of textures and of making room for the other person sonically. If I’m playing a busy bass line, Chris will stay out of my way, and vice-versa.”

While their joint repertoire started out being mostly based on Máire’s traditional material, it is now much wider than that and a typical concert consists of quite a few traditional sets from Ireland and Scotland, a bluegrass piece or two, maybe a swing tune, some original compositions that could be in virtually any style, and even an excerpt from a Handel violin sonata. Máire has had to learn to navigate the genres in the same way Chris has, and that has brought its own challenges. The harp is tuned diatonically (i.e. like the white keys on a piano, without sharps and flats). To get those extra notes the harp uses levers at the top of each string, and you can see harp players moving them up and down to get the notes they want - difficult enough in any situation, but a real feat when done often and done at speed, as is often the case with Máire when she is playing some of the swing jazz stuff. “I had to work at developing very fast lever-changing to facilitate all that chromaticism!” she says. Just watch her playing on YouTube to see how amazing she is at this – it’s astonishing.

In another important phase of their career, Chris and Máire joined forces with Máire’s sister, fiddle player Nollaig Casey, and her husband, the now sadly missed Arty McGlynn, in The Heartstring Quartet. Máire has also played as a trio with Nollaig and her other sister, Mairéad. A recent ‘SéMo Laoch’ documentary on TG4 celebrated Máire and Nollaig’s musical achievements and shows just how well-respected each of them is. The programme can still be viewed on the TG4 Player.

Obviously, life as busy touring musicians has been quite different of late, and Chris and Máire have had to adapt to life in COVID times. Chris has been working on his Bach project, and continues to teach his University of Newcastle students via Zoom. “It’s better than nothing,” he said, “but still not as useful as being in the same room as the student. However, the plus side is that I no longer have a 2½ hour commute to and from Newcastle. I can make it into the studio in about 90 seconds!” The duo did a gig for an organisation called Irish Music And Dance in London, as part of their series of online concerts in February and March. This concert was filmed on location at The Courthouse Arts Centre in Otley. “It was really fun to do a gig with stage, lights, PA etc,” said Máire. “The only thing missing was a live audience. Like all musicians, we’re so much looking forward to getting to play for live audiences again, whenever that might be!”

That is the question everyone wants the answer to. What happens next for Chris and Máire will very much depend on what happens, not just in the UK, but globally. “We were four weeks into a six-week tour of the USA when the pandemic struck,” Chris told me. “How long it’s going to be before we can tour the USA again is anyone’s guess. As for Europe…”

But luckily for the pair, though they still need to survive, they determined long ago that money was not going to be the main motivating factor in their career plans. Back in the 80s, Chris said that he’d “rather play interesting music than pursue interesting pay checks” and since then he has spent his time playing the music he loves rather than chasing commercial success. Together, Chris and Máire have created a career doing this, in many ways carving a new niche, and have managed to travel the world doing it – playing in around 23 countries up until now. Have they chosen the right career path? “Overall it’s been fine,” says Chris. “The commercial world that occupied much of my time until the mid- eighties was not by any means my favourite thing. It paid very well, but musically was not particularly interesting. Life since 1988 or so has been a lot more rewarding. We’re lucky really as we don’t owe anybody anything and generally have a pretty nice time.”

One of Chris’ solo CDs is called ‘Still Getting Away With It’. This may well be a tongue in cheek reference to his choice of career path. I’d argue that Chris Newman and Máire Ní Chathasaigh are doing far more than just getting away with it. They are setting the standard, and they are setting it high.

www.maireandchris.com

Photos: Con Kelleher